The Washington Post’s recent decision to adopt a new slogan – “Democracy Dies in Darkness” – captured a broader movement. Against ubiquitous complaints that virtually everything under the sun is “fake news,” many have sought to not only participate in and donate to causes more, but more routinely support supposedly high quality media. Here’s the problem: there isn’t any.

I can almost hear the shocked “-but but but but but!” Yes, you should still stay informed. As much as possible, you should still read or listen to free media, and even subsidize a local paper or two, as well as donate to public broadcasting. You need to be informed to act rationally, effectively, even safely in our increasingly volatile society.

That doesn’t mean chucking out your misgivings about the media. If anything, from prolonging your dives into the news, you should come back with even more. Just earlier this week, I decided to try to give, purported paragon of journalism, the New York Times yet another chance to win me over. They had put together a piece on an effort to account for government spending and its macroeconomic effects. Here’s a choice selection:

“When Mr. Ballmer retired as chief executive of Microsoft in 2014, he was only 57 and quickly realized ‘I don’t, quote, ‘have anything to do.” As he looked for a new endeavor — before he decided to buy the Clippers — his wife, Connie, encouraged him to help with some of her philanthropic efforts, an idea he initially rejected. […] Mr. Ballmer plans to make public a database and a report that he and a small army of economists, professors and other professionals have been assembling as part of a stealth start-up over the last three years called USAFacts. The database is perhaps the first nonpartisan effort to create a fully integrated look at revenue and spending across federal, state and local governments. […] Mr. Ballmer said he wanted the project to be completely apolitical. He has given money to candidates on both sides of the aisle.”

Let’s file this under landings not stuck. How does donating to one major political party and then the other somehow cancel out? Why would that leave you, rather than someone deeply entrenched in politics, a totally non-partisan, non-political seeker of truth? Why is the presumption that if you aren’t involved in elections you aren’t involved in politics? These aren’t debatable beliefs, but ones that speak to a particular isolation – from contempt for the political and electoral process, its collusions with other forms of institutional power, most blatantly with the power of money to bend ears and shape realities.

The reporting does improve from there, as Ballmer cites how the project changed political opinions he had before he started it, and the Times gently alludes to that being a political impact. Except, the New York Times wasn’t quoting him self-describing this as apolitical. They labeled him such and demonstrated it with a donation history. The confusion between non-partisan and apolitical was theirs, not his.

So one major political-minded newspaper has trouble not confusing their basic political concepts, but there’s gaggles of others who are sticklers for this sort of thing. One I suspect will soon become a household name is Clare Malone, senior political writer for FiveThirtyEight. Just yesterday, she corrected the grammar of another host on that site’s political-focused podcast.

But then again, the languages we speak are tools not physical laws – confusing socio-political concepts isn’t the same thing as confusing whether a pronoun should be nominative or oblique. In fact, she almost took pride in failing to pronounce the names of French candidates over the course of the episode, alluding to a similar pride in failing to pronounce French and Dutch in an earlier one as well.

This echoes, a bit less seriously, her advice to the Democratic Party after Trump’s minority coalition win – to talk less about the rights of people that others won’t be familiar with, namely transgender people. At the end of that day, is Malone informing the public with her commentary, or reassuring them that ignorance (whether about how to pronounce or foreign word or gender another person) is socially permissible? If her writing and media appearances are a product, what is their purpose? Its reflexive demonstration or defense of ignorance seems a far from something informative.

The conclusion that what the media is selling the vast majority of the time isn’t knowledge or useful analysis is fairly inescapable. Much of the time what’s being said rests on layers of puzzling semantic decisions and distinctions – often, all to make a point simply designed to be knocked down. Even when you don’t have to wade through those, what you ultimately yank out of the thicket of poorly conceived notions isn’t insight but an attempt at persuasion of (or worse, prostration to) an audience.

If the media is an industry, its product isn’t made of what it supposedly is, and it doesn’t do what it supposedly does. That sounds like almost any other industry in this country though, right? From food, to medical care, and even to learning what’s happening in the world, basic essentials that people need in this country are delivered by private industries that sell-up knockoff products and tightly cloister the parts that you actually need to live. You still need what they’re selling, at the end of the day, so you have to shop around, and buy the least toxic, most usable one you can find. You don’t have to like it. But, until things change, you have to do it.

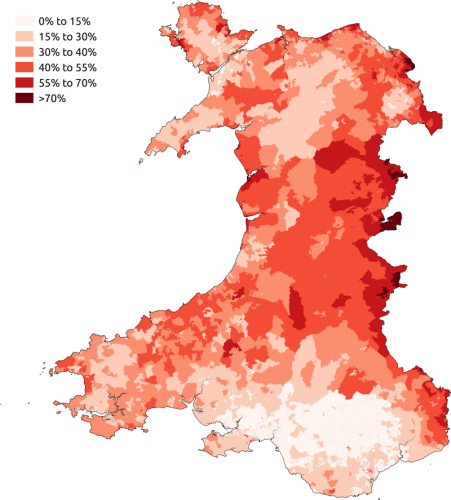

(Credit to Quinn Dombrowski, from

(Credit to Quinn Dombrowski, from  (The Princeton Election Consortium’s

(The Princeton Election Consortium’s  (A 1937 Nazi poster describing Jewish people as having “typical external features”.)

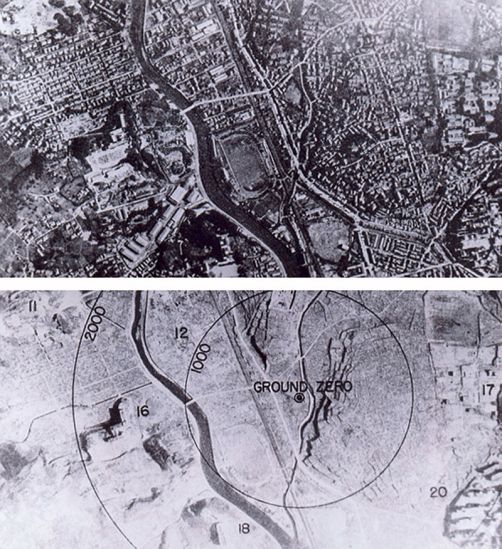

(A 1937 Nazi poster describing Jewish people as having “typical external features”.) (Nagasaki, Japan – before and after nuclear bombing.)

(Nagasaki, Japan – before and after nuclear bombing.)